Rankin Inlet

Kangiqtiniq

So in 1906, Roald Amundsen became the first person to sail across the North West Passage. His journey took him through what would become Nunavut (mostly) one day, but at the time, was called the Northwest Territories, ever since Britain had ceded the British Arctic Islands to Canada in 1880.

Of course, as far as Roald was concerned, the route he went through was Norway, since he was the first to sail it, and he was Norwegian. The Doctrine of Discovery held that the first Christian, or at least white person, to sail to a place owned it. But technically that would mean that it was jointly owned by Iceland, Norway, Denmark and Sweden because the Vikings were the first Christians to land on Helluland, later known as Baffin Island.

And to the south, the Monroe Doctrine held that anything that happened in the Americas by any foreign power that could conceivably upset the sovereignty status quo was America's concern. So they would be quite within their rights to take over the Northwest Passage in order to keep it from Norway.

Meanwhile, the local Inuit were pretty certain who owned the land - it is called Our Land in Inuktitut. It had been their land ever since they had wrested it from the Thule, who had taken it from the Dorset, who had either taken the land, or simply evolved, from the Pre-Dorset. So the issue of sovereignty in the Canadian north was a little muddy.

For instance, just before Roald's successful passage, Otto Sverdrup had been exploring the far north of Canada. He mapped, named and claimed the Sverdrup Islands for Norway, which claim went unpursued for a long time because what could you possibly use high arctic islands for. But it turns out that what you can use them for is bargaining chips, if what you're really after is other uninhabited and uninhabitable volcanic islands. So in 1930 a kind of a swap occurred. Norway relinquished any claims to the Sverdrup Islands; the UK relinquished any claims to the Jan Mayen volcano in the North Atlantic and the Bouvet volcano in the South Atlantic. Jan Meyen actually has quite the history, being code named Island X for a time, but let's leave that for another day. Today is about sovereignty and borders.

The border between Canada and Denmark is the Kennedy Channel between Greenland and Ellesmere Island. And right smack in the middle of the channel is the little barren rock of Hans Island. When the border treaty was signed in 1973 they couldn't decide on Hans' status, so it was left out of the agreement. Which led Canada to claim it in 1984 by planting a flag and leaving a bottle of Canadian whisky for visitors to enjoy. Which led Denmark to also plant a flag and to leave a bottle of schnapps, along with a letter of welcome for anyone visiting Denmark (they left our flag). This violent and dark episode in Canadian/Danish relations has come to be known as the Whisky War. And while it is ongoing there haven't been any further hostilities, and the whole sordid affair is likely to be resolved peacefully, perhaps over drinks. But there is more serious trouble on the horizon.

Roald proved that the passage around the top of Canada was navigable but far from practical in 1903. But since then the ice has been melting; the passage is becoming increasingly practical. In 2013, the Nordic Orion navigated the route. It sat too low in the water to transit the Panama Canal, which at the time had a maximum permissible draft of 12.04 meters, approximately 40 feet. But the canal is mostly fresh water, and is, of course, in the tropics. And that means the 40 foot draft was in units called TFW - tropical fresh water.

Draft lines on ships are marked in several units. At the top is TF - Tropical Fresh. Then you have F - Fresh. Then T - Tropical (salt). Then S - Summer, W - Winter, and finally, WNA - Winter North Atlantic. This is called a Plimsoll Line, after Samuel Plimsoll, who successfully campaigned to have these safe draft lines permanently marked onto hulls so anyone could tell at a glance whether the ship in question was overloaded. He started his campaign after the tragic loss of the London, a "coffin ship" bound for Melbourne (we'll talk more about those when we get to Australia) which was dangerously overloaded and sank as a result. Anyway, the upshot is, boats float higher in cold salt water than they do in the Panama Canal. So as ships become larger and ever more heavily loaded, a route that avoids the tropical fresh water of the Panama Canal with its modest maximum drafts becomes more important. And nowhere is the water colder or saltier than in the Northwest Passage.

There are currently 5 routes (actually six - route three comes in two flavours) to transit your ship through the top of Canada. Route 2, starting in the McClure Strait, has what they call multi-year ice, so shipping would require a dedicated ice breaker. Route 3A, starting in Lancaster Sound, is a viable route but with a draft limit of ten meters. Route 3B follows the James Ross Strait. This is the route Roald Amundsen took, and also the MS Explorer, which in 1984 became the first cruise ship to transit the passage. It has some shallow bits and hazardous navigation. Route 4 starts on the east side of Somerset Island and passes through the Bellot Strait, which is narrow and has very strong currents. Route 5 has the advantage of giving access to Hudson's Bay, starting as it does in the Hudson Strait, but you generally cannot proceed west out of Hudson's Bay through the Fury and Hecla strait due to ice. That leaves route 1.

Route 1 starts by travelling up the east side of Baffin Island past Iqaluit, Pangnirtung, Qikiqtarjuaq, Clyde River, Pond Inlet, Nanisivik and Arctic Bay, all Inuit communities. Then it proceeds through Lancaster Sound and Barrow Strait, just to the south of Cornwallis Island and the hamlet of Resolute, Canada's second northernmost civilian community. Viscount Melville Sound leads to Prince of Wales Strait at which point you leave Nunavut and are in the Northwest Territories near Ulukhaktok. Then you're in the Amundsen Gulf, clear of the Arctic Archipelago (if not the ice) and somewhere between Paulatuk and Sach's Harbour. The entire route has a limiting depth of 32 meters, which is 7 meters deeper than the draft of the Seawise Giant, the largest ship ever built. Ships taking the NWP can shave more than 3,500 nautical miles and twenty days off their journey (depending very much on where they start and where they're headed, of course). And there are no practical limits on ship size or draft. Also, the route has an anomalous number of Innuit communities, considering it's the high arctic. We'll get back to that thought in a moment; for now back to the Panama Canal.

The Canal is not a charity. It makes around two billion dollars a year, and Panama itself gets around eight hundred million of that. They may or may not be concerned that developments in Canada's high arctic could impact their bottom line; in any event they have recently completed an overhaul of the canal and it can now accommodate ships of up to 370 meters in length with drafts of up to 15.24 TFW. But the only limit on Canada's Route 1 is ice. And there are icebreakers. As the ice continues to melt Canada's high arctic waterways are becoming valuable. For whoever owns them.

So far no one is challenging Canada's sovereignty over the land of the high arctic. That will probably come later; there may be as much as 35 trillion dollars worth of resources buried there. In the meantime, though, sovereignty revolves around the water. Canada maintains that the passages through the Arctic Archipelago are internal waters; others, such as the States, maintain that they are international waters. The difference, of course, is whether people have to pay to make the passage and whether we can deny passage to warships.

In 1994, the UNCLOS, the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, came into force. It specifies exactly how sovereignty plays out for countries who are bordered by salt water, using carefully defined boundaries based on continental shelves and what-not. In very broad strokes, a country has full sovereignty over internal waters and no foreign vessel may traverse those waters without the sovereign nation's leave. Next come Territorial Waters, 12 nautical miles out from the shore. While Innocent (non-threatening) Passage is allowed for all vessels, the sovereign nation is allowed to regulate use (charge money) and specify routes. Archipelagos are a special case, and are considered to be a little bit Internal Waters and a little bit Territorial Waters; in any event, under the laws and control of the sovereign state.

After Territorial Waters comes the Contiguous Zone, between 12 and 24 miles out from shore. A nation can impose a limited subset of its laws in the Contiguous Zone, and it can detain vessels that have or are likely to break any laws within Territorial Waters. After that comes either the Exclusive Economic Zone, 200 miles offshore, or the Continental Shelf, whichever is further from shore. These zones have lessening powers until, past either the EEZ or the Shelf, one enters the High Seas, which have their own rules and ruling bodies, such as the International Seabed Authority, which controls access to things like mining in international waters. The wording for this body is contained in Part XI of the 1994 UNCLOS agreement, and it is Part XI that the United States has a problem with, and why it is not a signatory to the entire UNCLOS agreement. Which is why it doesn't recognize Canada's sovereignty over its Arctic waters.

China, on the other hand, jumped on board the UNCLOS agreement right from the get-go. They claim sovereignty over 90% of the South China Sea, mostly because of their artificial islands that make an archipelago of sorts. It was pure serendipity that they were asked to sign a western law that would forever muddy that issue.

Russia, though, like the States, has never signed UNCLOS. They have a much more direct approach to border disputes than some countries and so didn't feel the need. But Russia did have a long standing disagreement with Norway, a member of NATO, over 175,000 square kilometers of Barents Sea which might contain oil. Russia acceded (agreed, without actually signing it) to the UNCLOS treaty in 1997 and by 2010 had reached an agreement with Norway, basically splitting the disputed region right down the middle.

So both China and Russia have to accept Canada's sovereignty over Arctic waters every bit as much as they accept Canada's sovereignty over Arctic lands. Which might influence their opinions on Canada's claim to the land. China, the world's largest manufacturer and exporter of goods, would save billions upon billions in shipping costs with a viable passage through free international waters to the north of Canada. They have declared themselves to be a 'near arctic state' and are developing their Polar Silk Road plan, a plan to use the Northern Passages (east and west) to get their goods to market faster and more cheaply. They have entered into a joint venture with Russia to develop reinforced cargo ships; sort of their own ice breakers.

Russia has its own Northern Passage and is likely not interested in ours; it is already one fifth Arctic. But it's after more. There are estimates of as much as 13% of the world's remaining (undiscovered) oil and 30% of its natural gas being buried under the Arctic seabed. And Russia has claimed pretty much all of the Arctic all around the pole and right up to the Exclusive Economic Zones of Canada and Greenland (since it agrees to be bound by the UNCLOS agreement). The thing about the exact location of Canada's EEZ, though, is that it very much depends upon whether Canada owns the Arctic Archipelago or not.

And whether or not China and Russia stay on their side of the pole, pretty much anything they do, especially as partners, causes the Monroe Doctrine to start tingling south of the border. There are aircraft carrier strike group operations being conducted in Arctic waters, and the States considers our Arctic waters to be international waters, and not subject to the Innocent Passage clause of the UNCLOS, which they in any event have not signed. So, for instance, submarines can transit submerged and unannounced. But even if a war ship were to fire their cannons continually during passage, they are still pretty much unannounced if no one is there to see them.

It has long been recognized that Canada's claim to the Arctic is only as strong as the people living there. So in 1953 and 1955, the Department of Resources Development relocated 92 Inuit from Inukjuak in Northern Québec to Craig Harbour, Grise Fiord and Qausuittuq (Place of Darkness - Resolute). They were promised better hunting and improved living conditions if they made the move, as well as the option to move back after two years if they chose to. Now, as it happens, the three locations they were being relocated to were all in the High Arctic.

The Arctic comes in three flavours. The Sub-Arctic is not technically in the Arctic, being just below the Arctic circle. It gets all of the cold but not the 24 hour darkness to be found north of the circle. There are certainly plants and quite often trees, along with all of the things that plants and trees support, like ducks. A little north, above the circle, is the Low Arctic. Here there are no trees, but still shrubs and small plants. Various deer such as Caribou eat shrubs and small plants, so they are to be found here. It can get pretty dark in the winter, but it can also get pretty light in the summer, so there can be a profusion of flowers and berries, which ptarmigans quite enjoy. If you travel north of the Low Arctic, you will find yourself in the High Arctic. Here, there are no trees. There are few plants. There are few animals. There is a lot of cold and dark in the winter, however.

So in 1953, seven Inukjuak families from the Sub Arctic, along with three Pond Inlet families from the near High Arctic to act as trainers, set out to live in the very far High Arctic, to defend Canada's claim to the north. They were joined two years later by four more families from Mittimatalik (The Place Where the Landing Place Is - Pond Inlet). Things did not go well.

The plentiful game the families were promised turned out to be pretty sparse. The families were told they could only kill one caribou per family and if they killed a muskox they may go to jail. There was no game that required any sort of liquid fresh water - so no mussels, clams, ducks or geese like they had back home. There were seals and polar bears, to be sure, but rather than take on a polar bear it was easier to scavenge the dump at the nearby Resolute military base. Of course, if they were caught doing this they would be punished and their scraps confiscated. True to the government's word, though, the families were free to return to their previous homes after two years. But they would have to pay their own way, and any money they had earned by trapping in those two years was absorbed into the Eskimo Loan Fund. Some made it back home by contracting tuberculosis, necessitating a trip south. Others found solace in alcohol when the RCMP opened a post complete with a bar. Family violence became endemic.

Things improved somewhat in 1988, when the federal government acknowledged its responsibility and relocated those who wished back to Inukjuak. By this time, many had put down roots in the new environment and chose to stay. But the abuse everyone had suffered at the hands of the government remained a sore point. In 1994, the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples determined that the Inuit involved had been misled and ill treated. This led, in 1996, to a Reconciliation Agreement along with ten million dollars and ultimately an apology.

But the real healing had been happening somewhat quietly in some parallel discussions. Ever since the relocations, discussions were being held about further dividing the Northwest Territories, excising a large chunk of its remaining lands to become a new territory under the control of the Inuit. It took almost a half century, but on April 1st, 1999, Canada's newest territory, Nunavut, came into being. A plebiscite had been held years earlier in anticipation of the split, and Iqaluit (previously Frobisher Bay) became the capital, getting 60% of the votes over rival Rankin Inlet.

So the board that is the Canadian Arctic has been set up and everyone has made their first move. China's move was to side with Russia because their claim to be any sort of Arctic state is just silly. Russia's move was to use the Continental Shelf clause of the UNCLOS agreement to pursue a claim of much of the Arctic, up to everyone else's Exclusive Economic Zones. The States' move was the same move they always make - a massive military presence that knows no bounds. But Canada's move may have taken the other players off guard. Canada gave control over the land and water that some dispute was ours, almost all of the Arctic Archipelago, back to the Inuit, who have a rock-solid claim to the land and the water going back thousands of years. For their part, the Inuit, whether it was a move or simply happened that way, chose as their capital the entrance way to all of the different routes of the Northwest Passage, and dotted the most likely route with settlements. And as an interesting side note, Canada's Inuit share cultural and linguistic ties with the Yupik people of Siberia. Game on!

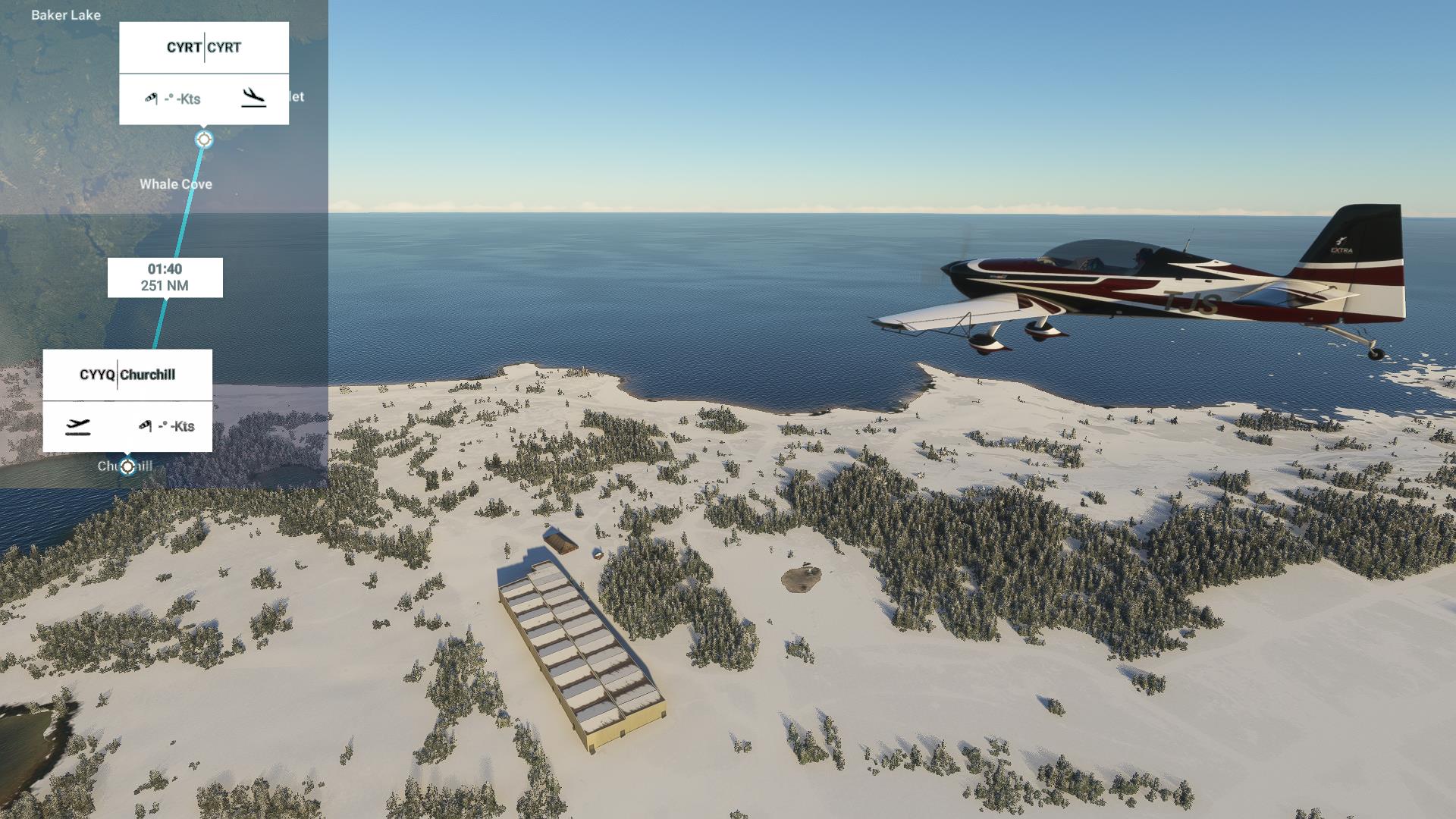

Anyhow, our next move is clear: off to Rankin Inlet. The one that didn't become the capital.

Farewell, Churchill.

Farewell, Churchill.

|

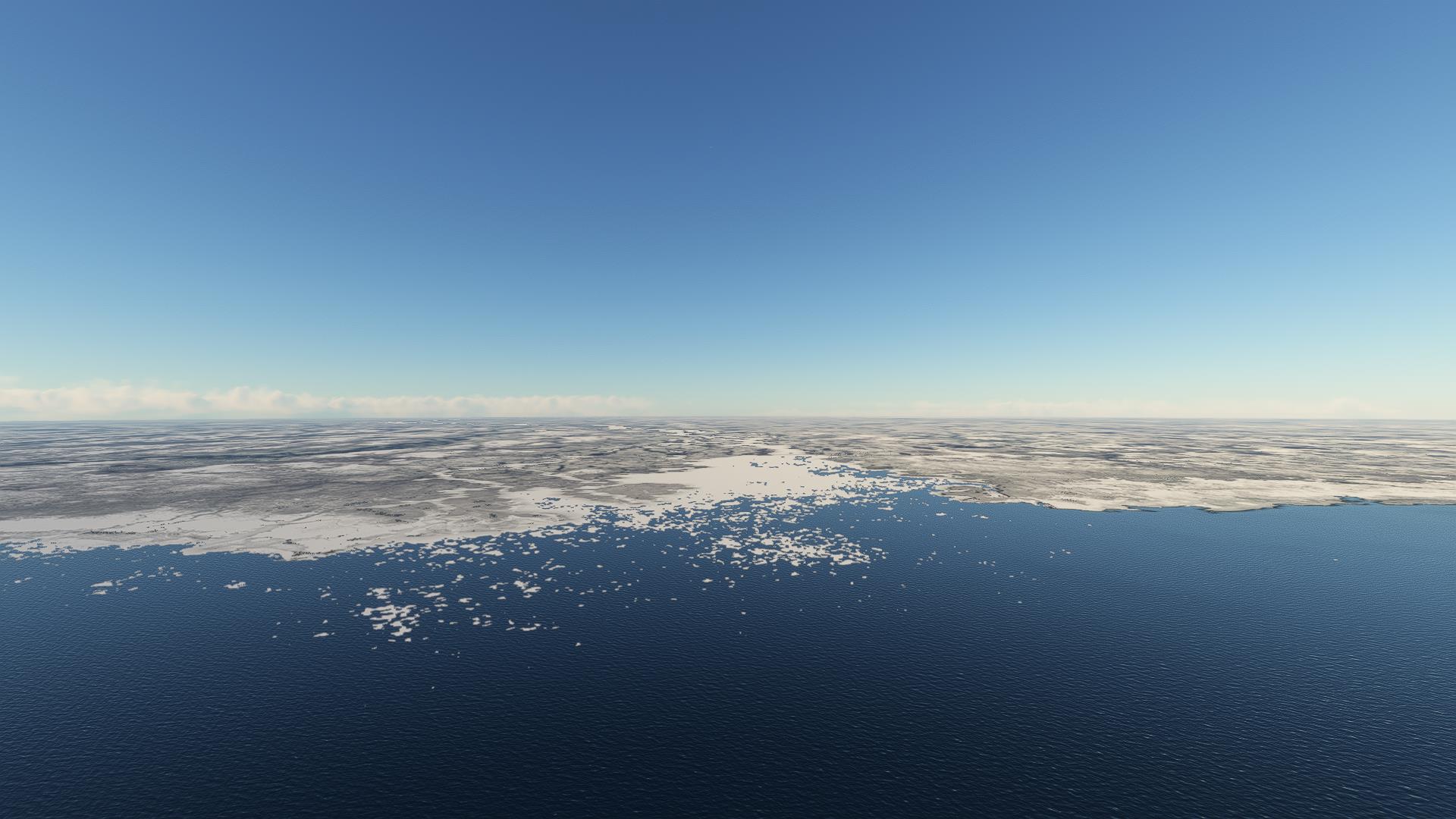

Another estuary.

Another estuary.

|

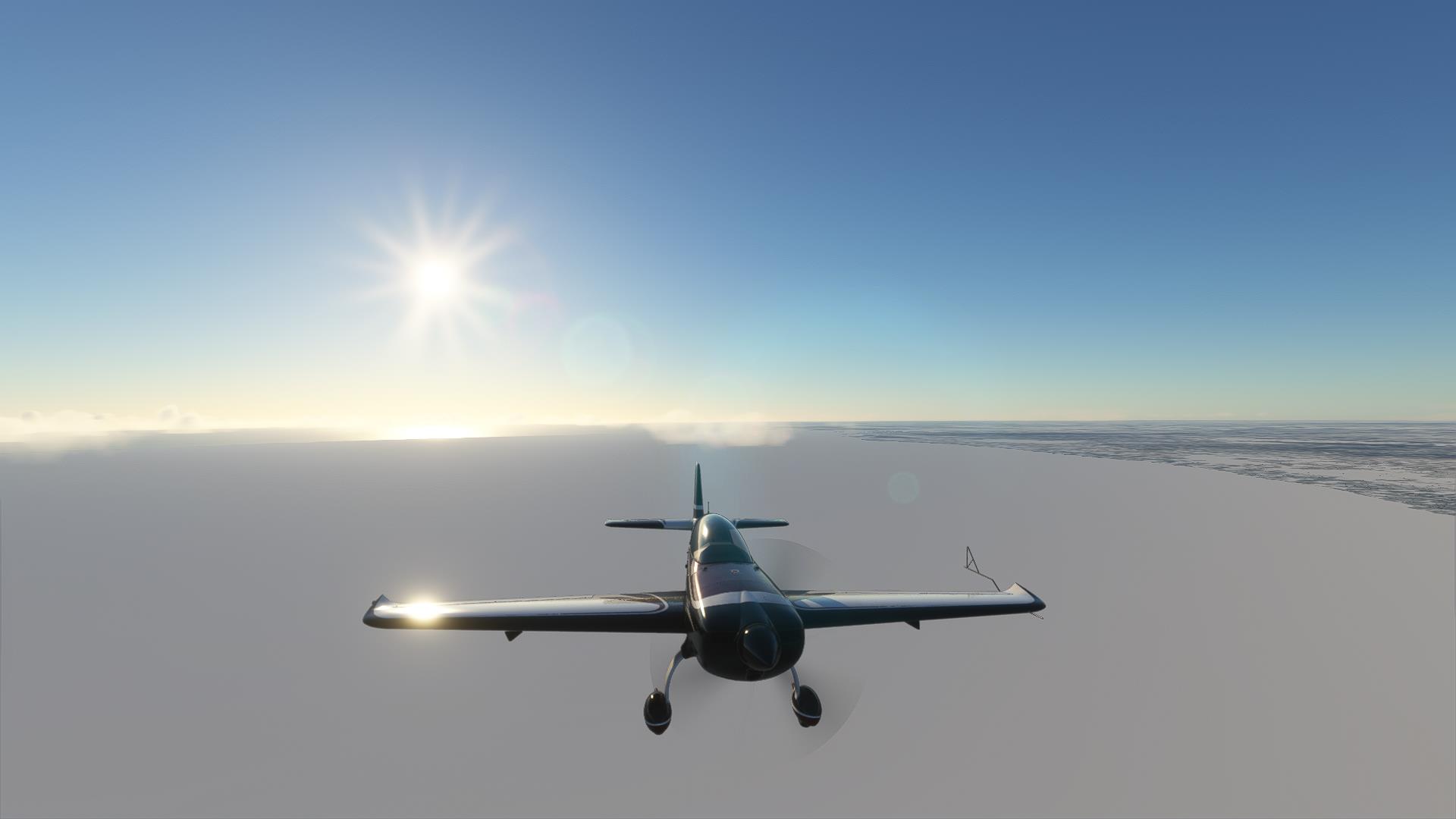

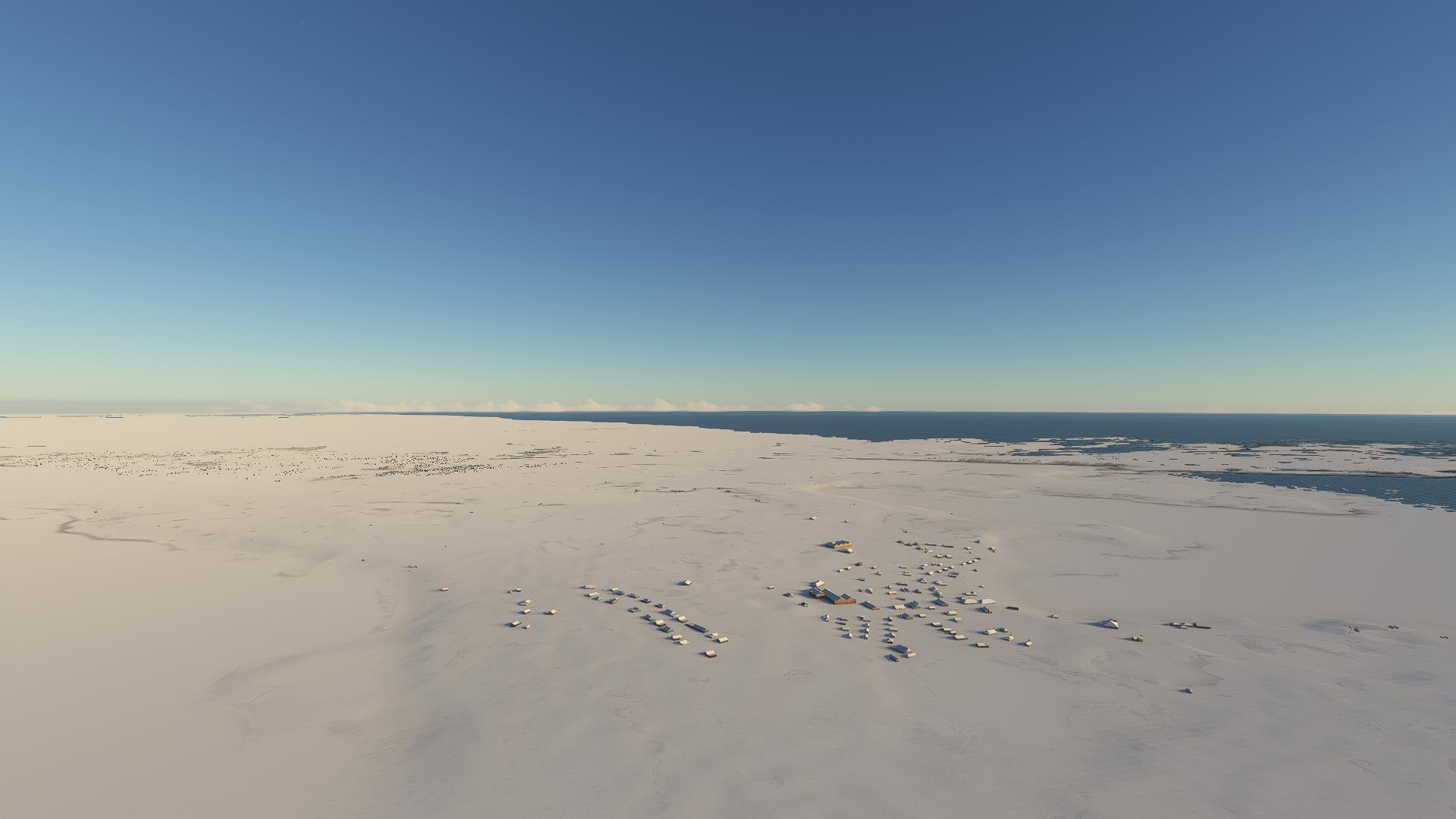

Ice as far as the eye can see.

|

|

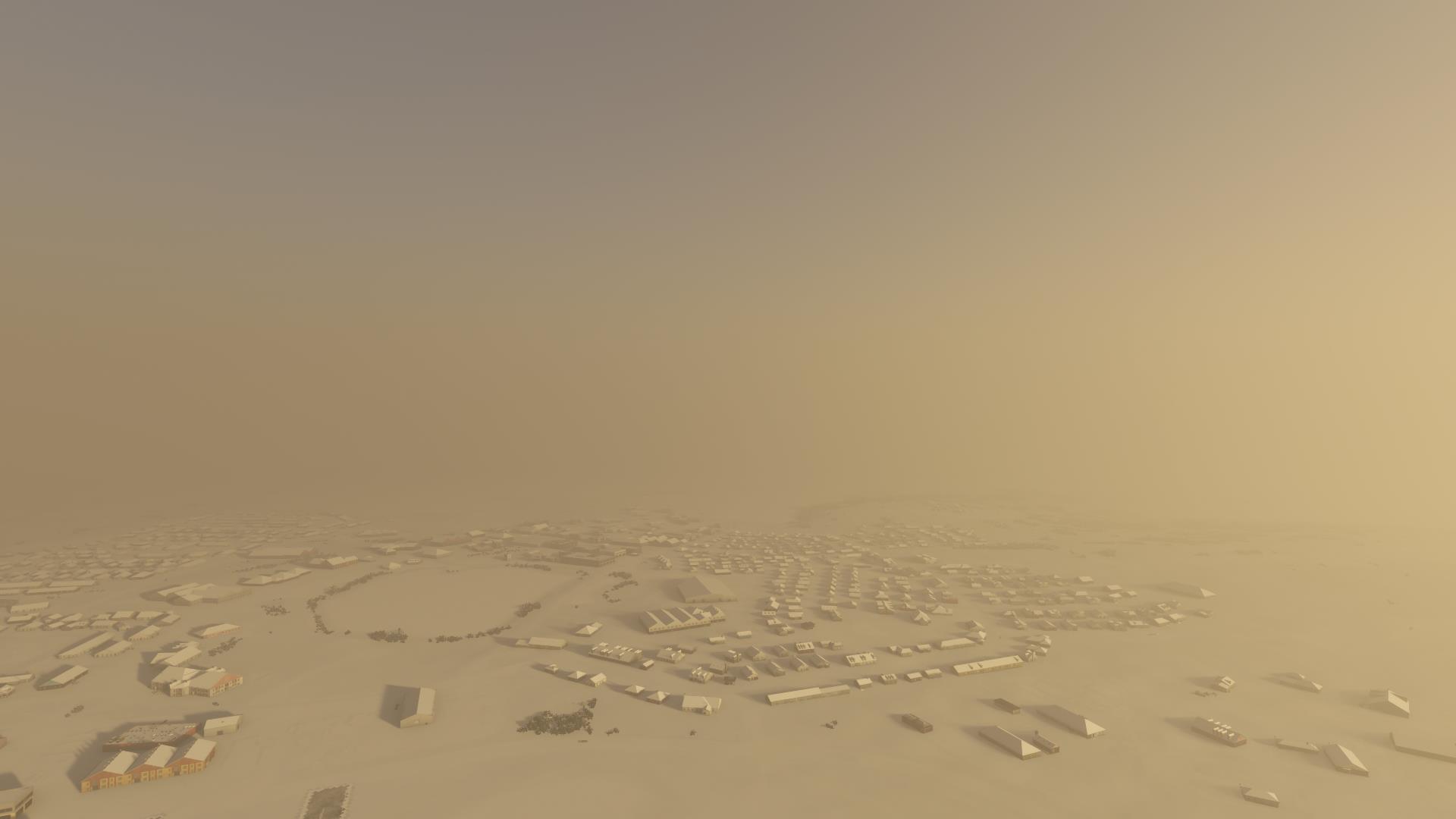

Arviat.

Arviat.

|

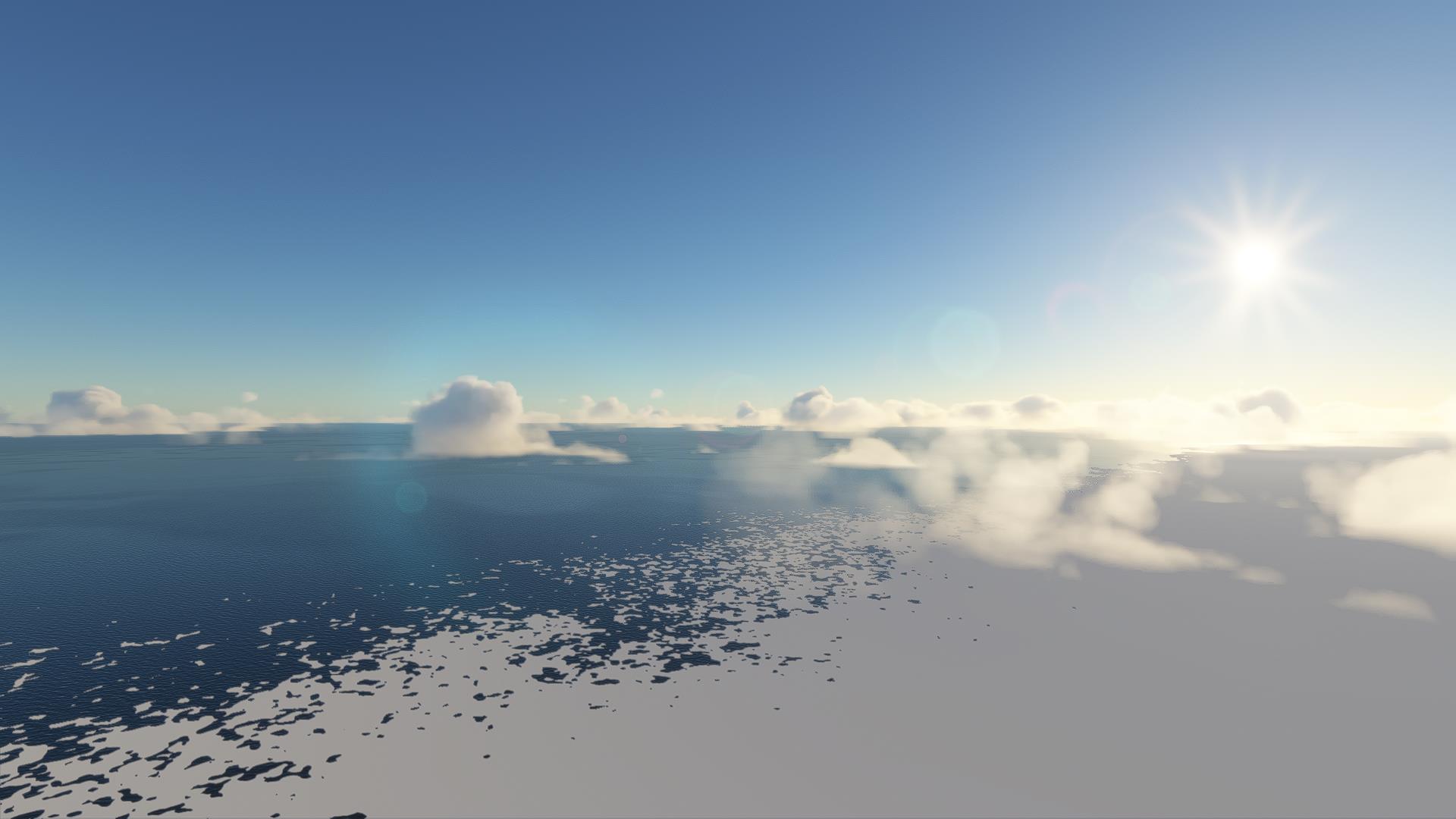

Whale Cove, with sea smoke up ahead.

Whale Cove, with sea smoke up ahead.

|

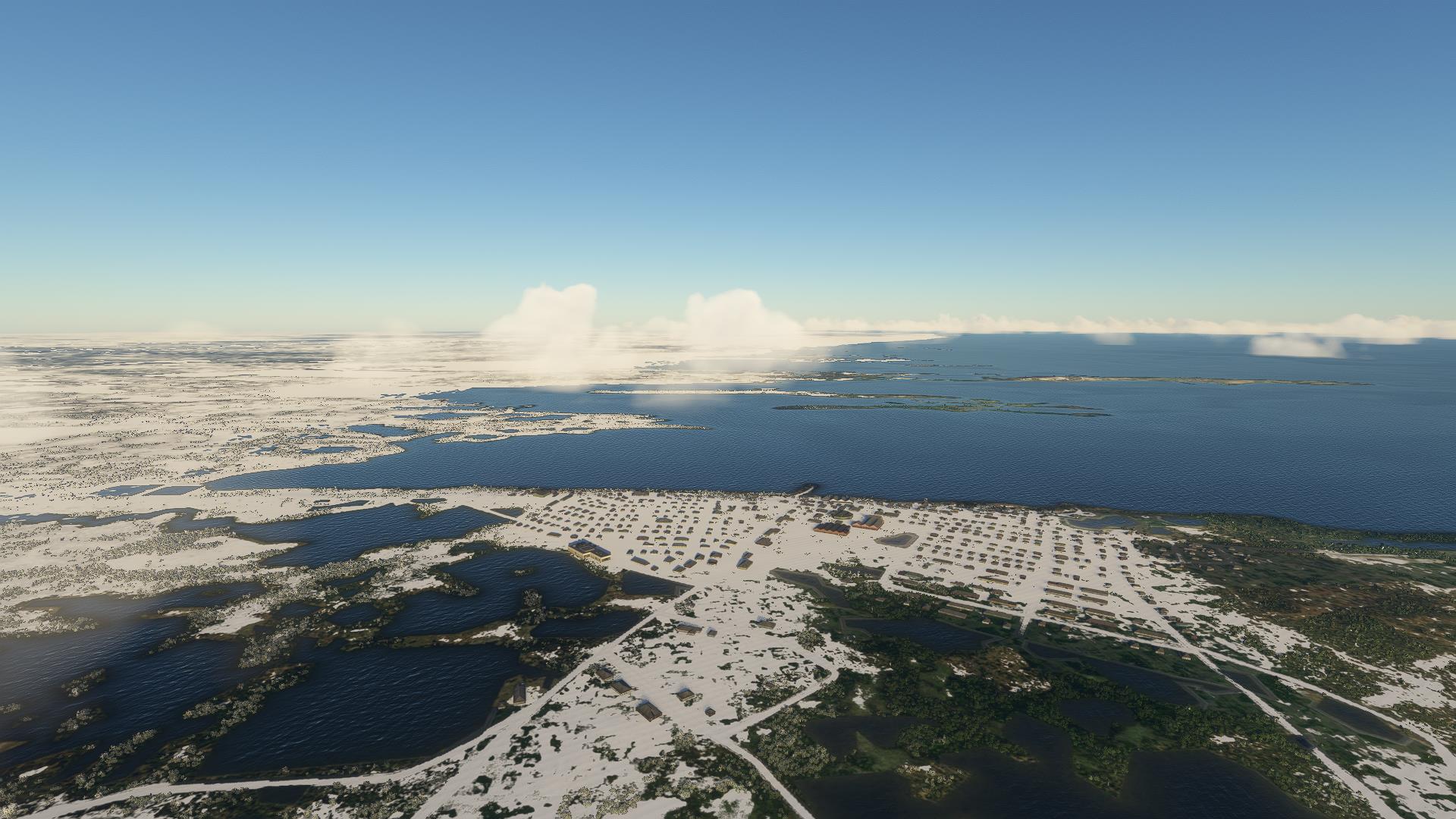

And here we are in Rankin Inlet.

And here we are in Rankin Inlet.

|

That's it for today. Tomorrow we'll start heading south.

That's it for today. Tomorrow we'll start heading south.

|